Del be Del / دل به دل

The Persian word for heart is ‘qalb’. When you talk about the throbbing, blood-pumping organ in the middle of your chest, ‘qalb’ is the word you use. But when it comes to what English-speakers know as matters of the heart, in Persian, they sit squarely in the del. When you're forlorn and missing someone, you're deltang — your del feels tight, not your qalb. When you sympathize with someone's misfortune, you're delsooz — your del burns for them. When you're overflowing with emotions and need to unload them, your del is por, or full. And the friend who listens supportively as you unload your woes is your deldar — they have your del.

Weaving Futures: A Conversation with Mika Benesh

ZAMAN Co-Editor Sophie Levy speaks with Mika about the title of their Judaica project, its connection to the concept of "Jewish temporality," practicing Jewish ritual as a trans person, and the value of participatory, inviting design.

Red Town

Misha shifts his weight from one foot to another. He holds his gaze firmly locked, and then sighs. He continues that his mother often recounted how “the camps were a reminder that all people can help each other out. Azeris, Estonians, Russians, Tatars – they were all in the camps alongside us – they shared their food with us, and we shared ours with them.” He says, “they joined Jewish celebrations, and my parents joined theirs.”

Iranian Jewry Beyond Meta-Narratives: A Conversation with Lior Sternfeld

Editors Evan Mateen and Sophie Levy met with Dr. Sternfeld over Zoom to discuss the ripple effects of the publication of his book Between Iran and Zion, the implications of studying Iranian Jewry as an Israeli scholar in the US, and the future of Middle-Eastern Jewish history as a discipline.

Babylon of the Tropics

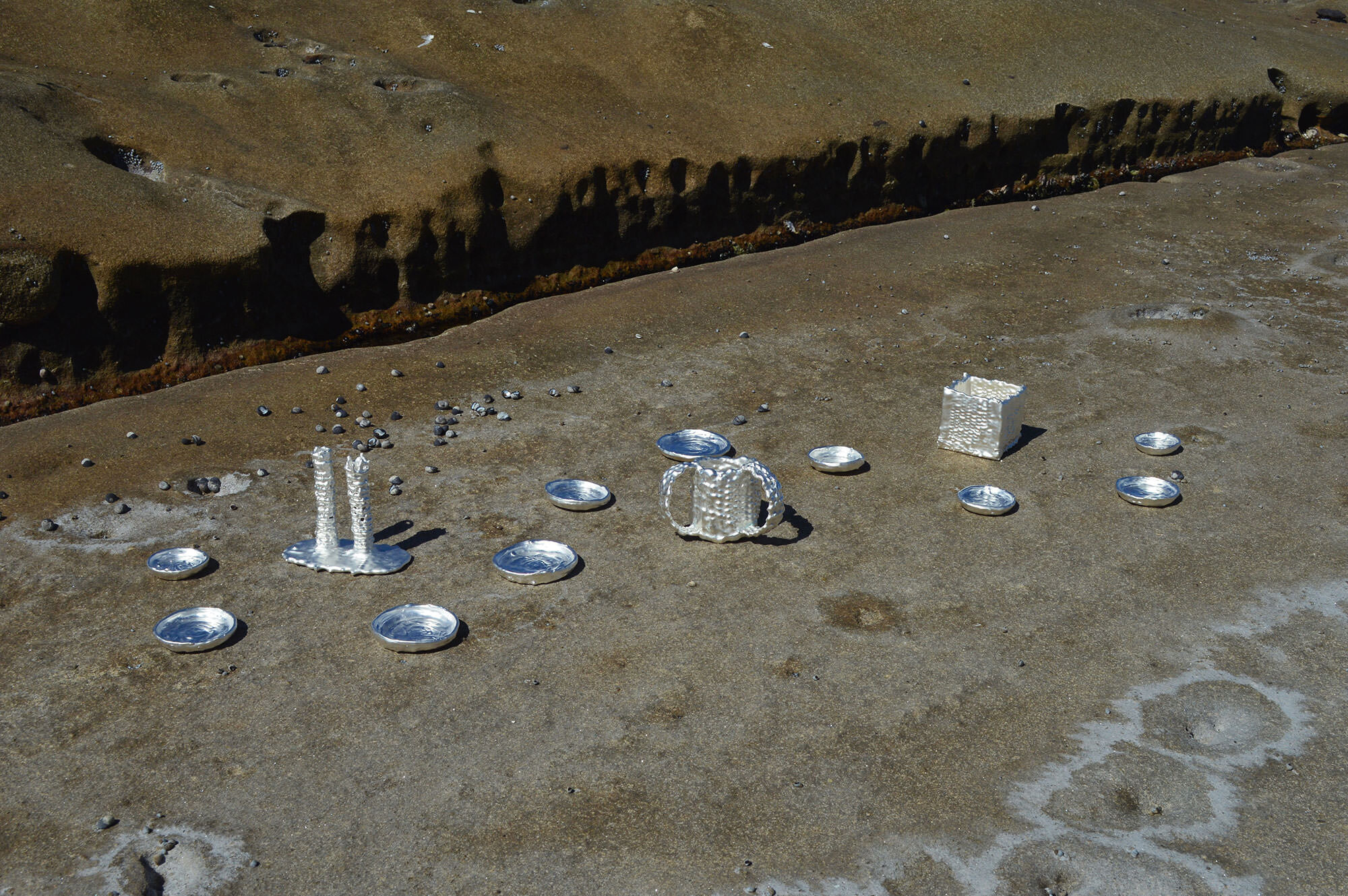

This series of artworks was influenced by my family’s history, which unfolds between the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish Empire, and the Republic of Brazil. My mother’s side of the family settled in Brazil after fleeing the Spanish Inquisition as marranos – Sephardim who moved through public society as Christians, yet secretly practiced Judaism in the privacy of their homes. My father’s side of the family came from Ottoman Syria in the wake of the Assyrian Genocide, and from Egypt after WWI.

Losslessness / An Arrow A Wing

I left my / Jewishness / for shame of / a broken story. / I return to these / details to understand / what was lost. / How we lost / our pathway back / through the hills / past an old border. / New borders / of mind / preventing / return.

Persian Liturgy and the Beauty of Forgotten Differences

Based on the siddur of Saadia Gaon, Persian liturgy developed over hundreds of years into a distinct rite entirely separate from those of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Yemenite Jews. Persian Jews generally sat on the floor, removed their shoes in synagogues, and likely regularly engaged in full prostration. But genizah manuscripts reveal fascinating variations in language and Persian Jewish tradition that suggest our forgotten heritage is a unique one among modern Jewish communities.

Existing in Duality: A History of Mashhadi Jewry

The lives of Mashhadi Jews had been a mystery since the day they were forcibly converted to Islam, a day often referred to as Allahdad, or God’s Justice. These newly converted Muslims were called jadid al-Islam and could be seen observing Ramadan and buying halal meat from the city’s markets. Little did the surrounding Shia Muslim community know what lengths the Mashhadi Jews went to preserve their Jewish faith and identity behind closed doors.

“The Full Severity of Our Connection:” Kayla Cohen on Her Debut Book

Cohen’s book focuses on the fundamental question: What defines Jewish peoplehood/personhood, if, at different places and points in time, it couldn’t so clearly be defined in resistance to an “other?”

On Language, Gender, and the Stigma of Mizrahi Sentimentality: An Interview with Ayelet Tsabari

It's rare for English-speaking audiences to find prosaic accounts and imaginations of Mizrahi life written by an Israeli author that were originally composed in English, rather than translated from Hebrew. Ayelet Tsabari's work offers us a glimpse into her life as a Yemeni woman born in Israel not only by way of content- but by way of language; Hebrew makes itself subliminally known in her writing.